A ceramic glaze is a covering or coating of a material that has been fired & fused to pottery. A glaze can be thought of as a chemical formula because, after applying a glaze & going through the firing process, it causes a chemical reaction in which the glaze is fused to the pottery & provides a durable surface.

Why did the ceramic artist break up with their glaze? – Go to bottom of page for answer!

What Is A Ceramic Glaze?

Glazing earthenware, for example, allows them to store liquids. A glaze can be used to tint, or embellish, an object and comes in a variety of finishes, such as glossy or matte.

After applying a glaze and putting the object through the firing process, which causes a chemical reaction and frequently results in a change in color. A glaze can be thought of as a chemical formula.

It also provides a more durable surface. Stoneware and porcelain are also coated with glaze. Glazes may generate a range of surface finishes, including degrees of a glossy (gloss surface) or matte finish and color, in addition to their functioning.

Glazes can also be used to accentuate the underlying design or texture, whether it is unaltered or engraved, carved, or painted.

Except for pieces in unglazed biscuit porcelain, terracotta, or other varieties, most pottery created in recent decades has a glaze.

The surface face of tiles is usually almost coated, and the new architectural terracotta is frequently glazed. Glazed brick is also popular.

Many ceramics used in industry, such as ceramic insulators for overhead power lines, are typically glazed, as is domestic sanitary ware.

What Are Ceramic Glazes Made Of

Ceramic glazes are made up of a ceramic flux. The flux is the main ingredient that promotes melting under high temperatures.

What Are The Main Ingredients In Different Colored Glazes?

Ceramic glazes’ main ingredients are often made up of silica, which serves as the primary glass formed. In addition, there are metal oxides such as sodium, potassium, and calcium that function as fluxes, lowering the melting temperature. And another important ingredient in colored glaze is alumina, which is frequently obtained from clay, stiffens the molten glaze and keeps it from flowing off the object. Other ingredients are used to alter the visual appearance. These are colorants such as iron oxide, copper carbonate, or cobalt carbonate, as well as tin oxide or zirconium oxide.

Glazes must contain a ceramic flux, which promotes partial liquefaction in the clay bodies and other glaze ingredients.

Fluxes reduce the glass’s high melting point, forming silica and, in rare cases, boron trioxide. These glass shapes might be included in the glaze elements or extracted from the clay beneath.

To alter the visual appearance of the fired glaze, colorants such as iron oxide, copper carbonate, or cobalt carbonate, as well as opacifiers such as tin oxide or zirconium oxide, are utilized.

To alter the visual appearance of the fired glaze, colorants such as iron oxide, copper carbonate, or cobalt carbonate, as well as opacifiers such as tin oxide or zirconium oxide, are utilized.

What Are The Different Types Of Ceramic Glazes?

I’ll cover 5 major categories of traditional glazes, each is named for its primary ceramic fluxing agent:

1. Ash Glaze

So let’s start with the Ash glaze. Ash glazes are ceramic glazes created from various types of wood or straw ash. They have traditionally been prominent in East Asia, particularly in Chinese, Korean, and Japanese ceramics. The final color of wood ash is predominantly dark brown to green. Pots with these glazes have the color and texture of the earth. Ash glaze is different from other glazes—here is how: A natural ash glaze is created by the ash that naturally settles on pottery as it is being fired in the kiln. Ash tends to accumulate thickly on the shoulders of the pottery. It then trickles down the edges of the pottery.

Ash glaze, popular in East Asia, is easily created from potash and lime-containing wood or plant ash. Ash glazes are ceramic glazes created from various types of wood or straw ash. They have always been popular in East Asia, especially in ceramics from China, Korea, and Japan.

Many traditional East Asian potteries still use ash glazing, which has seen a big comeback in both the West and the East in studio pottery.

Concept of an ash glazed vase

Ash glaze is a glaze that uses organic ash such as paper and wood. The chemistry of different organic ash types varies dramatically for each type of wood.

Many potters employ fake ash glazes; these are formulated to emulate the appearance of an ash glaze.

Also, many potters employ the wood ash from their neighbors’ wood stoves.

Calcium oxide (CaO), also called “quicklime,” is one of the ceramic fluxes used in ash glazes. Most ash glazes are in the family of lime glazes, but not all lime glazes use ash.

Extra lime was added to the ash in certain ash glazes, which may have been the case with Chinese Yue pottery.

Chinese Yue pottery is a form of Chinese ceramics that consists of felspathic siliceous stoneware that is typically adorned with celadon glazing. Yue pottery is sometimes called “green porcelain” in modern writing, even though it is not really porcelain and the colors are not really green.

A reasonably high temperature of roughly 1170 °C is necessary, high enough to transform the body into stoneware or porcelain. High temperature proto-celadon glazed stoneware was made earlier than glazed earthenware.

How Is Ash Used?

The glaze has properties like glass and pooling, which bring out the roughness of the glazed pottery’s surface.

When the glaze is mostly composed of wood ash, the final color is predominantly dark brown to green. The pots with these glazes have the color and texture of the earth.

As the ash% goes down, the artist has more control over the color. When wood is used, the final glaze color ranges from light to dark brown or green if no other coloring agents are added.

The rice-straw ash glaze yields an opaque creamy-white glaze with a high silica content. If the ash is particularly thick, there may be enough phosphorus to produce an “opalescent blue” color; rice-husk ash is ideal for this.

“Natural” ash glaze from kiln ash tends to gather heavily on the shoulders of conventional forms of storage jars and begins to trickle down the vessel’s walls. Before putting them in the kiln, you could improve their look by tying straw plaits across their shoulders.

How Does A Natural Ash Glaze Differ From Other Types Of Glazes?

A natural ash glaze is created by the ash that naturally settles on the pieces as they are being fired in the kiln. This ash tends to get very thick on the pieces, especially on the shoulders of the pieces, and it starts to run down the edges.

2. Lead Glazes

Lead glazes can be either plain or colored and fired to a temperature of about 1,470 F. Lead glazes have been around for nearly 2,000 years in China and throughout the Mediterranean. After firing, the plain lead glaze is glossy and clear.

Concept of lead glazed goblet

Roman lead glazed pottery goblet late 1St century B.C.

Much of the Roman ceramic technology was lost, but the use of lead in glaze continued in the ancient Greek cities of Constantinople and Istanbul today.

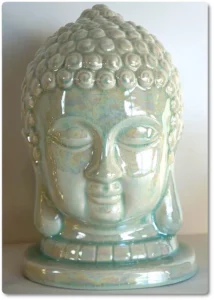

3. Porcelain Glazes

Porcelain glaze is a glass-like substance that was once used to seal porous pottery. Now, it is only used to decorate hard-paste porcelain, which is not porous.

When feldspathic glaze and body are fired together, they become inextricably linked. Feldspars are a class of rock-forming aluminium tectosilicate minerals that may additionally include sodium, calcium, potassium, or barium. Plagioclase feldspars and alkali feldspars are the most prevalent members of the feldspar group.

4. Tin-glaze

Tin-glazing is the technique of applying a white, glossy, ceramic glaze on clay pieces, which are often red or buff earthenware. Basically, in a nutshell, you can think of tin-glaze as a lead glaze with a trace of tin oxide added.

Tin-glaze is a lead glaze rendered opaque white by the inclusion of tin that covers the ware.

It was first used in the Ancient Near East and then became popular in Islamic ceramics; from there, it spread to Europe. Hispano-Moresque ware, Italian Renaissance maiolica (also known as majolica), faience, and Delftware are all included.

Tin-glazing is the technique of applying a white, glossy, and opaque ceramic glaze on tin-glazed clay pieces, which is often applied to red or buff earthenware. Basically, in a nutshell, you can think of tin-glaze as a lead glaze with a trace of tin oxide added.

Tin glaze’s opacity and whiteness promote its frequent ornamentation. Historically, this was done largely before the single firing, when the colors blended into the glaze, but since the 17th century, overglaze enamels with a light second firing have been used, allowing for a larger spectrum of colors. Common names for tin-glazed pottery include majolica, maiolica, delftware, and faience.

Certain types of pottery make use of both.When only lead is used to glaze a work, the glaze becomes fluid during firing and may flow or pool. Colors that have been painted on the glaze may also run or blur. Tin-glazing eliminates these issues.

The technique started in the Near East and made its way to Europe in the late Middle Ages, peaking in Italian Renaissance maiolica. East Asian pottery never used it.

Tin oxide is still used as an opacifier and a white colorant in glazes. Tin oxide has traditionally been used to create a white, opaque, and glossy glaze.

Tin oxide is used as a color stabilizer in some pigments and glazes as well as an opacifying agent.

Minor amounts are also employed in some electrical porcelain glaze conducting phases.

5. What Is Salt Glaze Pottery?

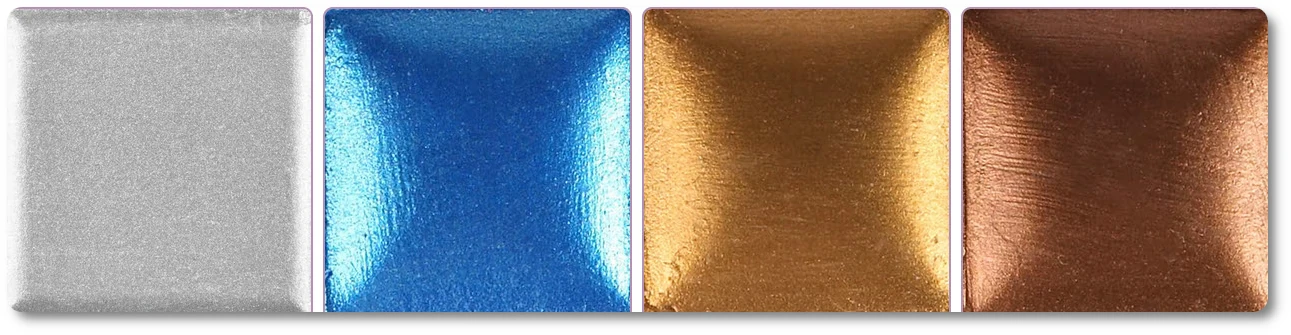

Salt glaze is stoneware with a glossy, transparent, and somewhat orange-peel-like glaze created by throwing common salt into the kiln during the higher temperature stage of the firing process. The sodium in the salt combines with the silica in the clay body to generate a glassy sodium silicate covering.

The glaze can be colorless or colored in various hues of a brown-like color (from iron oxide), a blue color (from cobalt oxide), or a purple color (from iron oxide) (from manganese oxide).

The glaze can be colorless or colored in various hues of a brown-like color (from iron oxide), and blue color (from cobalt oxide), or purple color (from iron oxide) (from manganese oxide).

How Is Salt Glaze Made?

Near the end of the firing process, the salt glaze is made on the unglazed body by the interaction of salt with the clay body’s elements, mostly silica.

The body should ideally be higher in silica content than standard stoneware, and iron impurities can aid in the production of effective salt glazes. Because reduced iron silicates are very powerful fluxes, the atmosphere in the kiln can be lowered.

A reducing atmosphere is a condition in which oxidation is prevented by the removal of oxygen and other oxidizing gases or vapors, and which may contain actively reducing gases like hydrogen and carbon monoxide, as well as gases like hydrogen sulfide that would be oxidized by any present oxygen.

When the right temperature is attained, often approximately 900 °C, the salting combination of sodium chloride and water is injected into the kiln. Or salt can be added within the kiln before firing.

As the kiln heats up to 1100–1200 °C, the sodium chloride vaporizes and interacts with steam to generate hydrogen chloride and soda.

These fumes react with the body’s silica and other substances. A glaze with a high alumina concentration and a low silica content is created, with soda as the major base.

The addition of borax, and sometimes sodium nitrate, to the salting mixture has enhanced salt glazes. Colored oxides can be added to the salting mixture to create ornamental effects, such as an aventurine coating.

Aventurine coating is a form of low alumina glaze with a high concentration of iron oxide.

How Are Salt Glazes Used?

Salt may also be used as a decorative feature on pottery. To easily make salted designs on biscuit crockery, just soak it in a brine solution. Other fabrics, like rope, can be soaked in brine and wrapped over biscuit crockery.

Salt can also be put in solution to color clay slips and dusted upon biscuit ware, which is in protective ceramic receptacles. Soda burning, a similar process, substitutes soda ash and/or sodium bicarbonate for ordinary salt.

While the application procedure differs slightly, the alternatives must be sprayed into the kiln; the effects are comparable to salt glazing, but with small variances in texture and color.

This method requires a kiln that you can spray into. Usually, these are large custom kilns with holes in various places in the kiln, allowing the spray to reach select areas of the pottery during the firing process.

While spraying the brine or salt glaze, wear protective gear, including special glasses. Some artists spend years perfecting this method. It can be quite intense and not for the faint of heart, as you are getting dangerously close to extremely hot surfaces.

What Are Some New Vitreous Glazes Developed Recently?

Hey, I know this is going to sound crazy, but there is a new type of glaze called Gloop. Gloop is a new glaze category.

It’s basically a really, really thick glaze.

The major advantage of Gloop is that two different colors may be placed close to each other and not bleed together.

So, for example, black and white may be placed next to each other without bleeding.

I find Gloop interesting, but that’s about it so far.

What Are The Benefits Of Using Ceramic Glazes?

A glaze can be used to tint, embellish, or waterproof an object. Glazing earthenware jars allows them to store liquids by closing the natural porosity of unglazed earthenware. It also provides a more durable surface.

How To Apply Glazes Properly

In fact, there are many more than 9 ways to apply glaze, but in this article I will cover 9 of the most popular ways to apply glaze.

Pouring Glaze

The first way, and definitely a fun way of applying glaze, is pouring. And it’s just like its name implies, you poor glaze directly onto your pottery. And that’s it. Often, a foundation coat of glaze is applied to cover the pottery first. Then you can start pouring.

While pouring, you can turn your pottery as needed. Then set it aside to dry. I like to work from a squeeze container. This gives me greater control over the glaze. I apply pressure to the squeeze container and apply the glaze along the pottery rim or body, and then allow gravity to handle the rest of the process.

I often apply a foundation coat of glaze to pottery or artwork first. Then I choose a glaze in a color that contrasts with my base. I like to work from a squeeze container. This gives me greater control over the glaze.

I really like this method because it does not take a large amount of glaze and I can fill up many squeeze bottles with different colors and apply them all at once. Using the squeeze bottle, you can get really creative.

Another method of pouring is simply pouring the glaze directly onto your pottery. This method does not use a squeeze bottle. Mix your glaze and then pour into a container suitable for pouring. Then just hold your pottery in one hand and, using your other hand, pour the glaze on the pottery.

While pouring, you can turn your pottery as needed. Then set aside to dry. While drying, look for unwanted drips or areas not covered and touch them up with a paintbrush.

Pouring Glaze Pros And Cons

| Pros | Cons | Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Great for applying glaze quickly | Not precise enough for detailed work | A high-quality squeeze bottle is necessary for control |

| It does not take a large amount of glaze | Can make a mess | Apply steady pressure |

| Can fill up many squeeze bottles with different colors | Not precise | Use paintbrush for touch-ups |

Dripping Glaze

Dipping might be the simplest way to create all kinds of special effects on your pottery or artwork. It’s easy because all you do is dip your pottery or artwork into a properly mixed bucket of glaze.

The hardest part is mixing the glaze to the right consistency. I have found through experience that thinner glazes work best for dipping. And small pottery, like cups and vases, also works best. They fit into the bucket and are easier to handle while dipping.

I like to use a Home Depot 5-gallon paint bucket with a good lid to hold the glaze. Then I take a pair of kitchen tongs and get a firm grip on the artwork and slowly lower it into the glaze, moving to the side while submerged, and then slowly lifting it out of the glaze.

I poured out the excess glaze inside the cup. I carefully set the cup or pottery to dry.

The biggest disadvantage to this method is the amount of glaze that is needed. You will need to mix up enough glaze to submerge your artwork. And that can be a lot of glaze. This is good for someone wanting to create a lot of pottery or art using the same color.

Dipping Glaze Pros And Cons

| Pros | Cons | Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Great for applying glaze quickly to many pots, etc. | Uses a lot of glaze | Consistency of the glaze is key |

| The simplest way to create all kinds of special effects on your pottery or artwork | Hardest part is mixing the glaze into the right consistency | Dipping is particularly captivating when there is a difference between the colors used |

| Creates a lot of pottery or art using the same color |

Brushing Glaze

It’s exactly as the name states. Just brush on the glaze. I use this method to apply the first coat of glaze to my artwork and, in some cases, also use a brush for decorating.

Just load up your brush and start painting. Be careful to avoid correcting an area too many times because it will show as streaked after firing. Normally, I apply anywhere from 2 to 3 coats, depending on the brand of glaze.

Brushing Glaze Pros And Cons

| Pros | Cons | Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Great for applying glaze precisely | Need good brushes and a steady hand | Avoid over-correcting and going over an area too many times |

| Simple and can apply many colors | Need a variety of brushes ranging from very small to large depending on the decoration | Apply anywhere from 2 to 3 coats depending on the brand of glaze |

Spraying Glaze

Spraying glaze requires an air gun. The glaze should flow through your spray nozzle and be of the consistency to not run down your pottery. I find spraying is great for applying a base layer of glaze. Take a bunch of pots, set them in a place where you can freely move around them, and start spraying. It’s much like using a spray can. You have to watch out for drips and runs.

The main thing to watch out for is making sure you mix the glaze properly. It should be well mixed, passed through a filter, and be of the right consistency. The glaze should flow through your spray nozzle and be of consistency not to run down your pottery.

Spraying Glaze Pros And Cons

| Pros | Cons | Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Great for applying glaze to many pots at once | Need a good air gun and there is a lot of over-spray | Consistency of the glaze is key. Strain your gaze so it passes through the air gun |

Splattering Glaze

Oh boy, we are talking Jackson Pollock style now, right? This sounds like fun. And well, it is if you like this type of result in your pottery. The idea is to make nice splatters and streaks across your pottery. Using many colors gets you that Jackson Pollock look.

There are many ways you can use to get the splatter effects. You can use a brush or a wooden paint stir stick.

Splattering Glaze Pros And Cons

| Pros | Cons | Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Great for applying glaze in a random-like pattern | All your work could end up looking like Jackson Pollock | The brush method requires a stiff paintbrush |

| Lots of fun | Can be messy | Don’t be afraid to experiment |

Brush Method Of Splattering Glaze

Load up your paintbrush with paint. Good brushes to use are stiff ones. Hold the brush about 6 to 8 inches away from your pottery and run your finger across the brush, at the same time using a flicking motion toward your pottery. Do this several times to achieve the desired effect. It’s always a great idea to test your pattern on a piece of paper or cardboard before doing it on your pottery.

Stick Method Of Splattering Glaze

Take a paint stir stick, like the kind they give you when you buy paint at the paint store. Set your pottery on a table about 6 to 8 inches from the edge. Dip the paint stick into the glaze and then hit it against the edge of the table. The glaze will splat onto your pottery. There is really no right or wrong way, so feel free to use your imagination and experiment.

Stippling Glaze

Stippling is a great method when you want to shade part of your artwork or pottery. The result you get is a brush-like texture finish that looks like shading.

Start by dipping just the tips of the bristles into the glaze, and then lightly dab the ends of the bristles on your pottery where you want shading. Be careful not to overload your paintbrush and not to apply too much at once. Otherwise, you lose the stippling effect.

The trick is to use a brush that does not shed bristles and is soft but not too soft.

Stippling Glaze Pros And Cons

| Pros | Cons | Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Great for applying shadows and shading | It’s hard to get the right amount of glaze on the end of the brush | The stippling method requires a good stippling paintbrush |

Sponging On Glaze

Sponging on glaze is a very popular method. To start, all you need is a good textured sponge and a container of glaze. The trick is to get the right amount of glaze on your sponge. If you overload your sponge, the end result ends up looking like a blob instead of a nice texture.

Sponging on glaze is a great way to make clouds and leaf patterns on your pottery. I have found synthetic sponges have a much tighter pattern than natural sponges because the sponge itself has a fine pattern. Natural sponges have a loose pattern.

It’s a great idea to test out your sponge pattern on a piece of paper or cardboard. And I have found it seems to work better if your sponge is a little wet.

Sponging On Glaze Pros And Cons

| Pros | Cons | Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Great for applying clouds and leaves | It’s hard to get the right amount of glaze on the sponge | Requires good sponges and practice |

| Very popular method | You have to test every sponge pattern on a piece of paper or cardboard | Synthetic sponges have a tighter pattern |

Slip Trailing or Glaze Trailing

Glaze trailing is a technique for drawing on pottery and or artwork by using a squeeze bottle with an aperture tip.

Start by filling a small handheld squeeze bottle with glaze and using the aperture tip like a pencil to draw glaze on your artwork or pottery. Once fired, the glaze stays on the surface, and you end up with a delicate line. You can use many colors and come up with many patterns or objects to draw on your pottery.

The trick to slip trailing or glaze training is that you need to have a steady hand, a good squeeze bottle, and a lot of practice.

Slip Trailing or Glaze Trailing Pros And Cons

| Pros | Cons | Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Great for applying lots of details and designs on pottery | It takes a steady hand | Looks easy but requires a lot of practice |

| Great technique for drawing on pottery | Must have good squeeze bottles | Constant pressure on the squeeze bottle is key |

| Can use many colors and can come up with many patterns | Takes a lot of practice to get good | Practice on paper first |

Using Wax And Glazing

Wax-resist is a product that does what its name implies. It resists glaze or repels glaze away from areas where it is applied. So, in essence, wherever wax-resist is applied, the glaze will not adhere.

Start by having pottery ready with a base coat of your color applied and fired. Or if you want to leave it naturally, then no base coat is needed. It’s your preference. Now you are ready to apply the wax-resist. Apply the wax-resist to areas of your pottery where you want the base coat color to show. You can use a paintbrush to apply wax-resist.

Just remember to have a separate set of brushes for wax-resist. After the wax-resist dries, apply your glaze color all over the pottery. Don’t worry about getting glaze on the part you painted with wax-resist. Next, clean up with a damp sponge. The wax-resist will burn off during firing.

| Pros | Cons | Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Great for applying different colored glazes next to each other | Requires purchase of wax-resist and an extra set of brushes | Do not use your glaze brushes to apply wax-resist |

Glazing Tips

- If there are any spots that were left untouched, you will need to go back and touch them up before the metallic or luster overglazes dry.

- Use either a yellow glaze or a yellow underglaze for the best results when applying solid coverage with gold or bright gold. For the best results, when applying solid coverage with White Gold, use either a gray glaze or a gray underglaze.

- If overglazes are applied inadvertently to the incorrect area, use a cotton swab to remove the color that was applied in error or let it dry and lightly scrape off.

- Work should be done in a spotless, dust-free environment that has enough ventilation. Before you can move on, your hands must not have any moisture, oils, or hand lotion on them.

- Because they include solvents, overglazes need to be applied in a location that has enough ventilation. Those who are more sensitive to smells, such as pregnant women, should take extra precautions to ensure that the spaces in which they are working have sufficient ventilation. Odors aren’t hazardous during the ring phase, although they can be very bothersome. Even though these smells dissipate rapidly, it is best to avoid working in the area around the kiln while it is in the process of ringing, unless the kiln has a vented hood and an exhaust fan.

Advice On How To Care For Your Ceramics Once Glazed

The same care should be taken with your overglazed items as you would with genuine china. Despite the fact that overglazed ceramics may withstand being washed in a dishwasher on a regular basis, the overglaze will ultimately wear away.

Overglazes are capable of being used on surfaces that are in direct contact with both food and drink. When cleaning overglazed ceramics, excessive scrubbing should be avoided at all costs due to the risk of removing a thin layer of shine from the glaze.

Troubleshooting Common Problems With Ceramic Overglaze

Troubleshooting Metallic Glazes

| Problems | Causes | Remedy |

|---|---|---|

| Crazing | If the crazing has sharp lines and looks like a spider web, it is in the metallic and was formed by a ring that was heated to high temperatures. Or the metallic finish was applied too strongly if the crazing is extensive and occurs in only a few lines. | To avoid any problems in the future, check that the metallic color is a red, use witness cone 019-018. |

| The appearance that is drab, smoky, or cloudy | Too much was applied. The kiln was loaded to its capacity or beyond. Incompatible glazing. | Allow 1” to 2” between pieces. Fire at witness cone 06. Do not reapply metallic. Cone 6 glazes (cone 6 glazes) fires to a slightly lighter color than cone 06 (2232F vs 1830F) does. |

| Cracks in the overglaze ring on the ware | Thermal shock. | Follow the right steps to avoid thermal shock. Be careful not to put objects too close to the kiln’s peephole or side. |

| Fish eyes are circular breaks in the metal that show the glaze underneath | Dust or lint on a wet metal surface; grease, oil, or water droplets on ware or on a brush. | If the piece hasn’t been fired yet, try to touch it up. |

| Purple hue | Too little of the metallic was used. | Use more metallic paint and re-fire. |

| The metallic shine is easy to remove | The temperature is not hot enough. | Add more metallic glaze and re-fire for cone 019. |

Troubleshooting Mother Of Pearl Glazes

| Problems | Causes | Remedy |

|---|---|---|

| Dusts or powders off easily | Glaze applied too heavily | Rub it off with a soft cloth, add a thin coat of luster, and fire again to witness cone 020. |

| Turns brown | Pottery was fired too close to the open kiln peephole | Move the piece away from the open kiln hole and re-fire to cone 020 |

| Looks like ice or frosty looking | Too hot firing temperature | Reapply luster, fire no hotter than cone 020 |

| Shadows or smudges looking blue or purple | Luster contamination | Remove luster, reapply, and re-fire, make sure brushes are clean and lint-free |

9 Innovative Ceramic Pottery Artists

Here are nine innovative ceramic artists that use glazes in different ways. Rather than using color to imitate nature or tell a story, as conventional ceramicists do, they use the glazes to manipulate the work’s surface. I recommend that you read the articles and get inspiration from their ceramic artwork.

Daniel Rhodes

Rhodes is best known for building up forms and textures with clay by using it like paint. Daniel Rhodes makes what he calls “fortuitous forms” of clay by applying slips in different ways.

Don Reitz

Don, known as the healing series. Reitz’s salt glaze process produces brownish “luminous colors with a dazzling surface.”

Elsa Rady

American potter. Elsa’s work progressed from useful to sparse, nonfunctional pieces. Elsa’s elegant and monochrome glazed ceramic vases were well known. Several of her works are in the collections of well-known museums in the United States. Ralph Bacerra, Otto, and Vivika Heino, and other professors inspired Elsa.

Rady’s work demonstrates that she was highly influenced by Chinese ceramics from the Song Dynasty (simple shape and form), as I learned after examining her work more closely. Rady’s ceramic artwork is a modern minimalist ceramic cup distinguished by vertical, precise geometric elements that serve no practical purpose.”

Kenneth Price

Kenneth Price is well-known for his small-scale ceramic sculptures that resembled biomorphic blobs, split geodes, and surreal teacups.

Mark Pharis

Mark is known for his slab-built geometrical teapots.

Richard Notkin

Richard Notkin is recognized for his intricate, meticulously crafted ceramic teapots with unglazed surfaces that include iconography.

John Mason

John Mason is well-known for his large-scale geometric wall reliefs and expressionistic sculptures.

Kirk Mangus

Kirk Mangusis is a ceramic artist and sculptor recognized for his whimsical, expressive approach and experimental glazing. Kirk’s work is distinguished by deep carvings of own characteristic motifs on well-known classical shapes on high-relief surfaces. Greco-Roman art, mythology, Japanese woodblock prints, comic books, and pottery from Mesoamerica to the Middle East and Asia inspire Kirk.

Noriko Kuresumi

Noriko Kuresumi is well known for her organic forms inspired by the ocean.

Definitions

Environmental impact of glazes – When non-recycled ceramic products are subjected to warm or acidic water, there is a greater possibility that components of the glaze will be leached into the surrounding environment. Heavy metals can be leached from ceramic objects if the glaze is applied improperly or if the products are broken. Lead and chromium are two heavy metals (metal compounds) that are often employed in ceramic glazes. Because of their toxicity and capacity to bioaccumulate, these two heavy metals are subject to stringent regulation by government bodies.

China Clay – Clay is the mineral form of kaolinite. It is a crucial component in the manufacturing process. It is a layered silicate mineral, having one tetrahedral sheet of silica connected by oxygen atoms to one octahedral sheet of alumina octahedra. In addition, it has one octahedral sheet of alumina octahedra. Kaolin, sometimes called china clay, is the common name for rocks that contain significant amounts of kaolinite. There are some people who still use the archaic name lithomarge to describe to kaolin. This phrase originates from the Ancient Greek litho- and Latin marga, which means’stone of marl.’ At the moment, the term “lithomarge” can be utilized to refer to a compressed and large kind of kaolin.

Fire Clay – The term “fire clay” refers to a variety of refractory clays that are utilized in the production of ceramics, most notably fire brick. Fire clay is described by the Environmental Protection Agency of the United States as a “mineral aggregate formed of hydrous silicates of aluminum with or without free silica.” This definition is quite broad.

Combustible Materials – When exposed to fire or heat, a combustible substance is a material that, in the form in which it is used and at the conditions that are anticipated, will ignite, burn, assist combustion, or emit flammable gases. Combustible materials include, but are not limited to, wood, paper, rubber, and plastics.

Potash feldspar and soda feldspar – The mineral group known as aluminum silicate of potassium, sodium, and calcium is referred to by its common name, “feldspar.” Ceramics and glassmaking are the two industries that make the most use of the mineral feldspar.

Silicon dioxide – The naturally occurring compound silica, commonly known as silicon dioxide, is made up of the two elements that are found in the greatest abundance on earth: silicon and oxygen. Quartz is the most common type of silicon dioxide that people are familiar with. It occurs naturally in water, plants, animals, and the ground itself, among other places.

Lithium carbonate – An example of an inorganic compound is lithium carbonate. The manufacturing of metal oxides frequently calls for the use of this white salt.

Chrome oxide – Inorganic compound that contains the element chromium. As a pigment, it is one of the primary oxides of chromium and is also employed in several processes. Eskolaite is a somewhat uncommon mineral that may be found in nature.

Lead oxide – An example of an inorganic compound is lead oxide, which is also known as lead monoxide. Because lead exposure is strongly linked to a variety of health problems, which are collectively referred to as lead poisoning, the disposal of leaded glass (most commonly in the form of discarded CRT displays) and lead-glazed ceramics is subject to toxic waste regulations. These regulations are in place due to the fact that lead exposure is strongly linked to a variety of health problems.

First Islamic opaque glazes – From the seventh century forward, glazed ceramics were frequently used in Islamic art and pottery, most frequently in the form of sophisticated pottery. This usage of glazed ceramics began about this time. Tin-opacified glazing was one of the earliest innovative technologies invented by Islamic potters. It was used on a variety of Islamic ceramics. The first examples of Islamic opaque glazes include blue-painted ceramics discovered in Basra during the 8th century. These examples date back to the Islamic period. Stoneware, which had its beginnings in Iraq in the 9th century, was an important innovation that also contributed significantly.

Are cone 6 glazes food safe? The Western Lead-Free Stoneware glaze series contains gloss, matt, transparent, and opaque glaze types. It was designed for clays that mature at higher temperatures and has a spectrum that goes from cone 4 all the way up to cone 6. The colors are safe for consumption and perform admirably on a wide range of clay bodies.

Bone ash – The calcination of bones results in the production of a white substance known as bone ash.

Vanadium pentoxide – The inorganic substance known as vanadium(V) oxide can be represented by the formula V2O5. Solid vanadium pentoxide is brownish-yellow in color but has a strong orange hue when it has just precipitated from an aqueous solution. This compound is more commonly known as vanadium pentoxide. As a result of the high oxidation state to which it has been subjected, it possesses characteristics of both an amphoteric oxide and an oxidizing agent.

Nitrous acid – Nitrous acid is a monoprotic acid that is exclusively found in solution, in the gas phase, and in the form of nitrite salts. It is a very weak acid. Nitrous acid is the key component in the production of diazonium salts, which are derived from amines. The diazonium salts that are produced can be used as reagents in azo coupling processes, which are what produce azo colors.

Nepheline syenite – Nepheline syenite is a kind of holocrystalline plutonic rock that is made up of nepheline and alkali feldspar to a significant extent.

Mullite crystals – Around one thousand degrees Celsius, the kaolin particles in conventional porcelain are transformed into lengthy mullite crystals during the fire process. Because of this transition, vitrified porcelain is far more durable than regular porcelain. When the transition takes place in porcelain, the material becomes more than just a collection of silica particles held together with feldspar-silicate glass; the mullite forms a fibrous mesh that significantly fortifies the matrix.

Magnesium carbonate – MgCO3, often known as magnesium carbonate, is a kind of inorganic salt that can seem colorless or white in appearance. There are also other hydrated and fundamental forms of magnesium carbonate that may be found in the form of minerals.

Titanium dioxide – Titanium dioxide, sometimes referred to as titanium(IV) oxide or titania, is an inorganic molecule that has the formula TiO 2 in its chemical make-up. Titanium white, also known as Pigment White 6 or CI 77891, is the name given to this substance when it is put to use as a pigment. Although some of its mineral forms can have a dark appearance, the substance itself is colorless and insoluble in water.

Uranium glass – Uranium glass is glass that has had uranium, often in the form of oxide diuranate, added to a glass mix prior to the melting process for the purpose of coloring the glass.

FAQ: What Ceramic Glazes are Made Of

What are the 3 main ingredients in glaze?

The three main ingredients in most ceramic glazes are:

- Silica (SiO2) – Silica is the main glass-forming component in glazes. It melts at high temperatures and creates a glassy surface.

- Alumina (Al2O3) – Alumina provides stability to the glaze, helping to prevent it from running off the ceramic piece. It also affects the hardness and durability of the glaze.

- Flux – Fluxes are materials that lower the melting point of the glaze, making it easier to apply at lower firing temperatures. Common fluxes include materials like feldspar, boron, and various metal oxides.

Are ceramic glazes made of glass?

Yes, ceramic glazes are essentially a type of glass. The primary component in glazes, silica, is also the main ingredient in most types of glass. When the glaze is fired at high temperatures, it melts and forms a glassy, vitreous surface on the ceramic piece. However, ceramic glazes often contain additional materials like alumina and fluxes, which differentiate them from pure glass.

What is the purpose of using a glaze on ceramics?

Glazing serves multiple purposes in ceramics:

- Aesthetic Appeal – Glazes can add color, texture, and a glossy finish to a ceramic piece.

- Durability – A glaze can make a ceramic item more durable by making it more resistant to wear and tear.

- Water Resistance – Glazes create a non-porous surface, making the ceramic piece water-resistant or even waterproof.

How do I choose the right glaze for my project?

Choosing the right glaze depends on various factors like:

- Firing Temperature – Make sure the glaze is compatible with the firing temperature of your kiln.

- Clay Body – The glaze should be compatible with the clay body you are using.

- Intended Use – If the ceramic piece will be used for food, make sure the glaze is food-safe.

Can I make my own glazes?

Yes, making your own glazes is possible and often encouraged for those who wish to experiment and customize their ceramic pieces. However, it requires a good understanding of the chemistry involved and access to raw materials and equipment. Always remember to test your glazes before applying them to your final pieces.

What are some common problems with ceramic glazes?

Some common problems include:

- Crazing – Fine cracks in the glaze surface.

- Crawling – Areas where the glaze pulls away from the clay body, leaving bare spots.

- Pinholing – Small holes in the glaze surface after firing.

Why did the ceramic artist break up with their glaze?

Because it was always too “cracked up” to be reliable!

Bonus – Why did the potter bring string to the studio?

To “tie” up some loose ends in his work!

References

Gloop Glaze: https://glazy.org/recipes/100382

Duncan Paint Store Mother Of Pearl Glaze: https://duncanpaintstore.com/mother-of-pearl

Duncan Paint Store Metallic Glazes https://duncanpaintstore.com/non-fired-products/ultra-metallics

Burleson, M. (2003). The ceramic glaze handbook: Materials, techniques, formulas. Lark Books. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=PiJEAhMxLQgC&oi=fnd&pg=PA7&dq=ceramic+glaze+in+art&ots=sa84Qy1NXo&sig=r-ddKGl5srBIW6RrCIELqF2NkAw#v=onepage&q=ceramic%20glaze%20in%20art&f=false

Wicks, J. L., & Coppage, R. H. (2021). An Introduction to Ceramic Glaze Color Chemistry. In Contextualizing Chemistry in Art and Archaeology: Inspiration for Instructors (pp. 403-424). American Chemical Society. pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/bk-2021-1386.ch016